Why is managing water to promote well-being difficult? Water is a distinct natural resource that delivers multiple functions and services at multiple geographic scales. Being essential for survival, it was recognised as a human right by the Action Plan from the United Nations Water Conference in 1977. At its source, in rivers, forests, wetlands, and soils, it provides ecosystem services and functions that are public goods. These include ecological functions such as pollination, biomass growth, soil productivity, and maintaining the energy balance on Earth through the different states of water (liquid, ice, vapour). It is also an indispensable input to all economic activity, with no close substitute.

Given the wide range of functions and services provided by water, its management requires balancing the often-competing goals of economic efficiency, equity, and environmental sustainability while navigating difficult trade-offs.

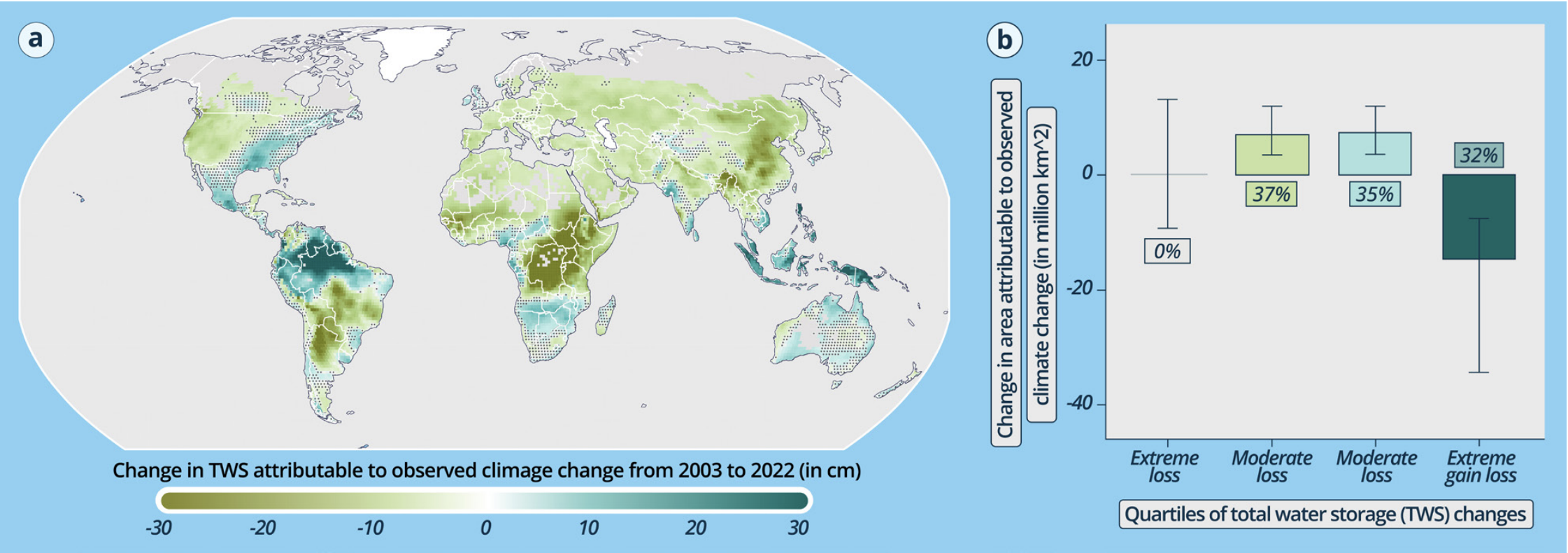

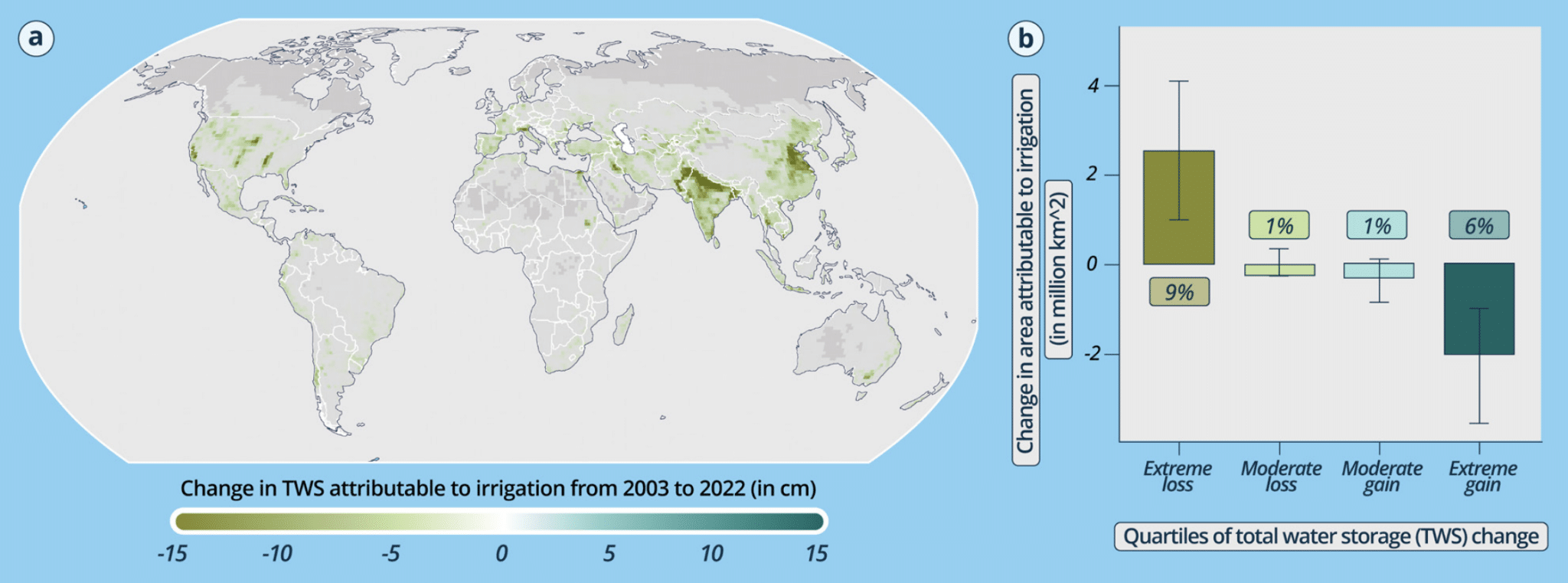

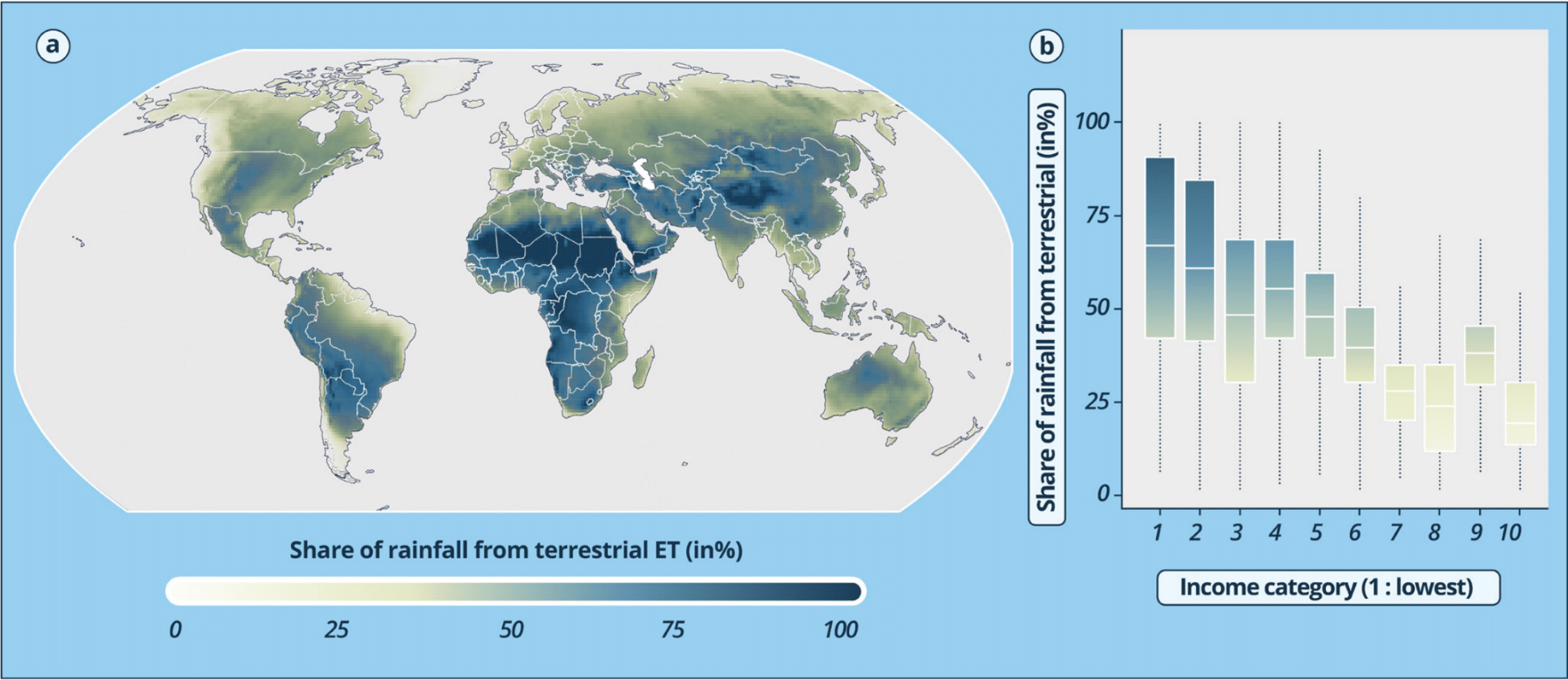

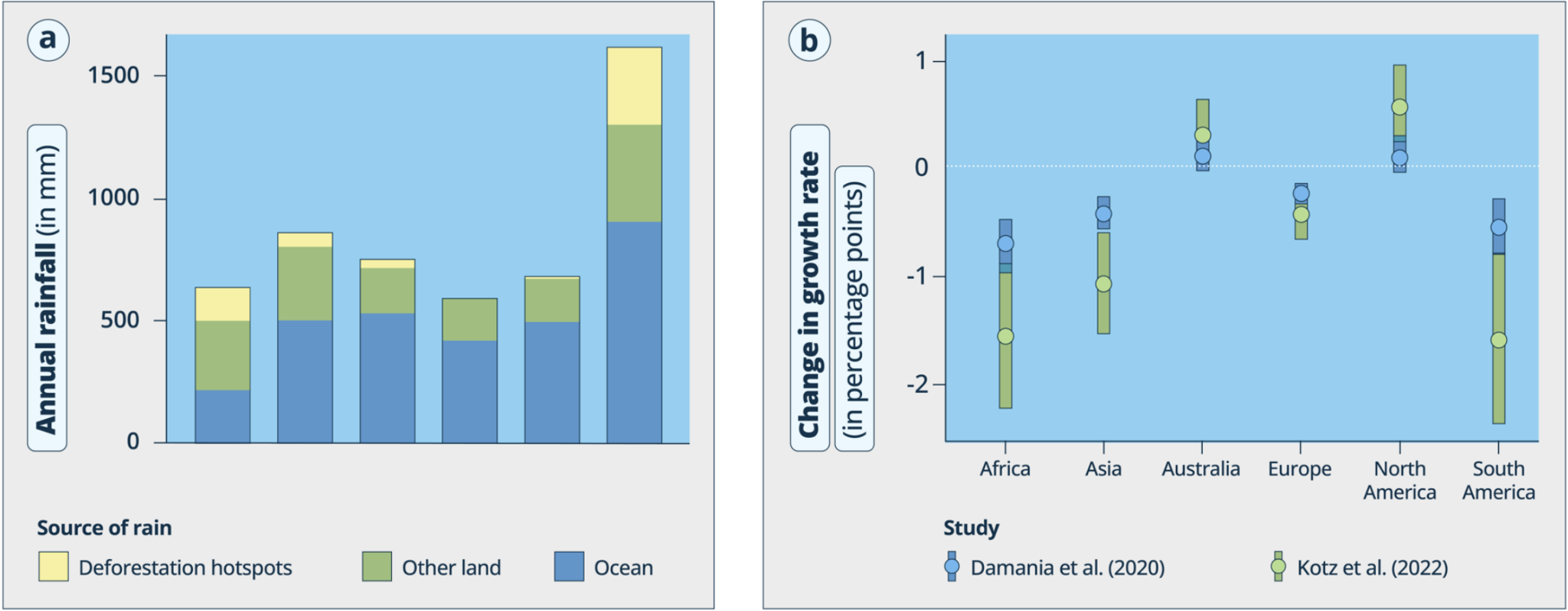

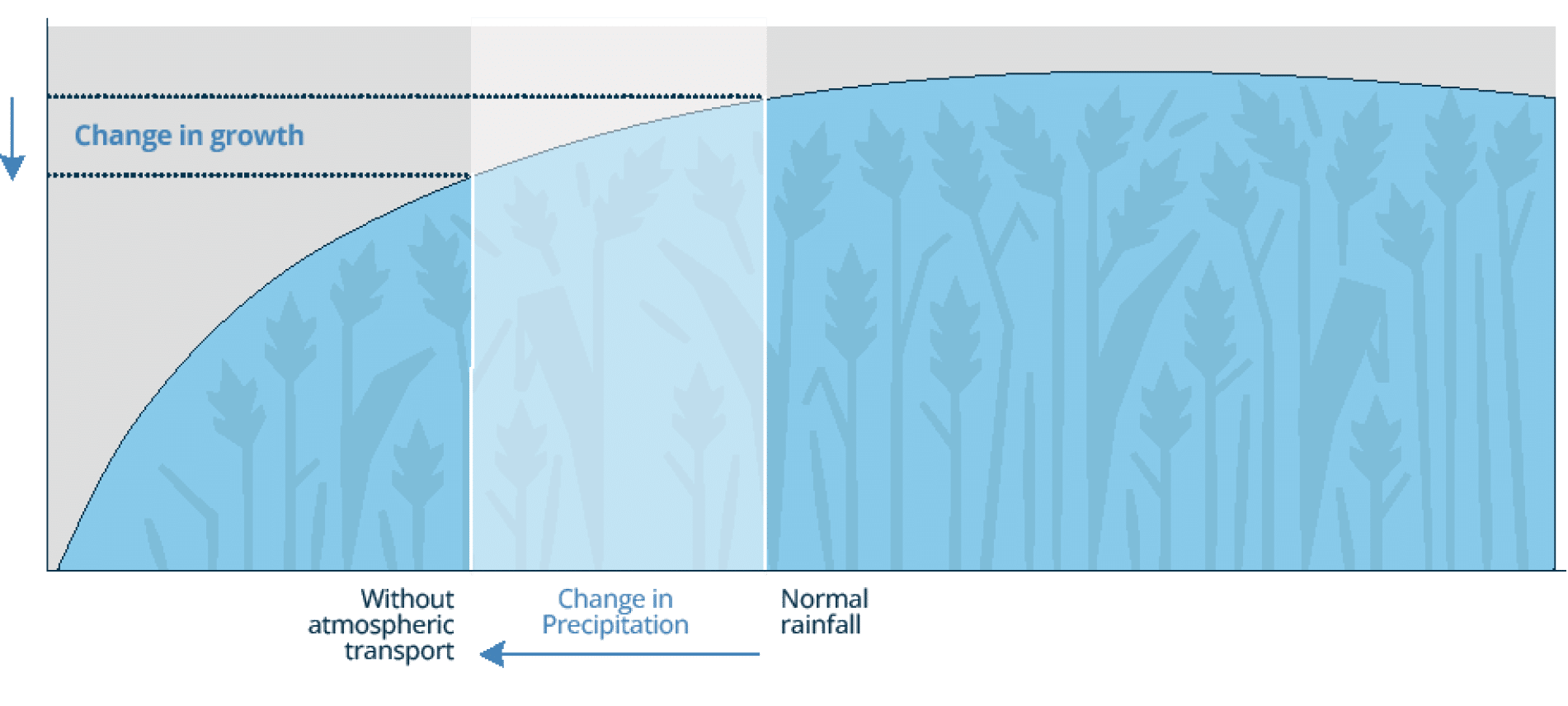

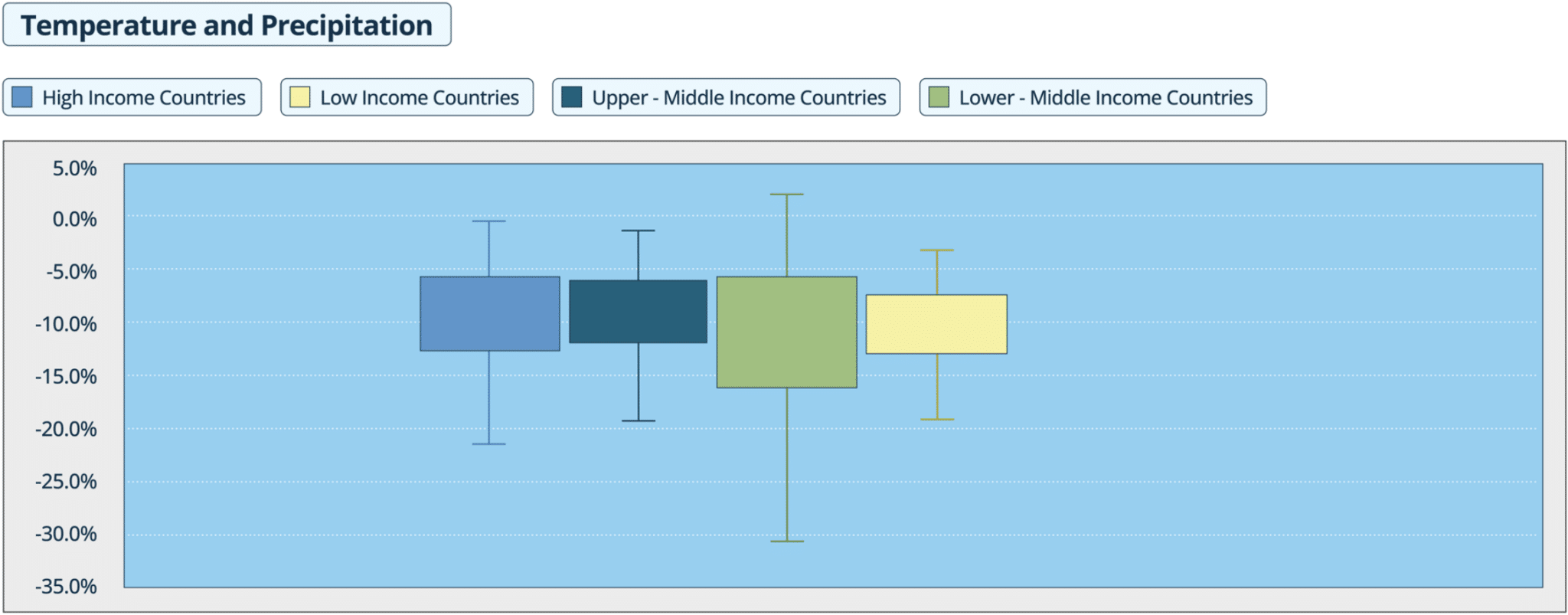

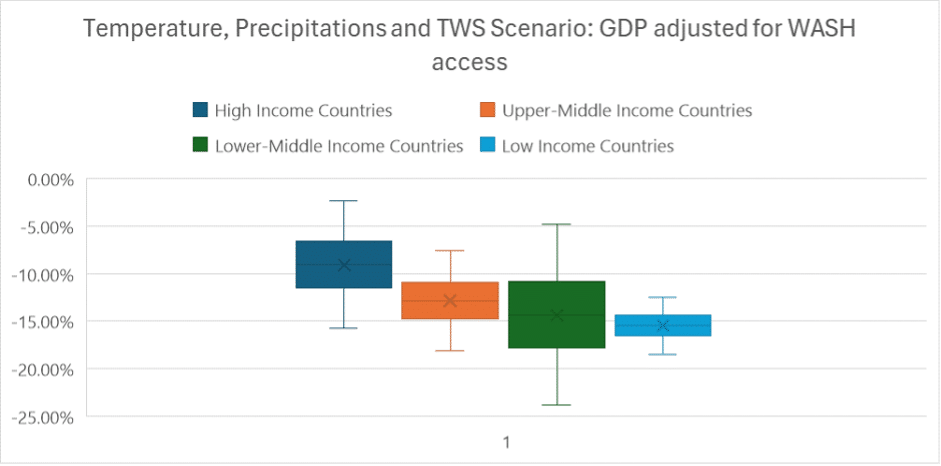

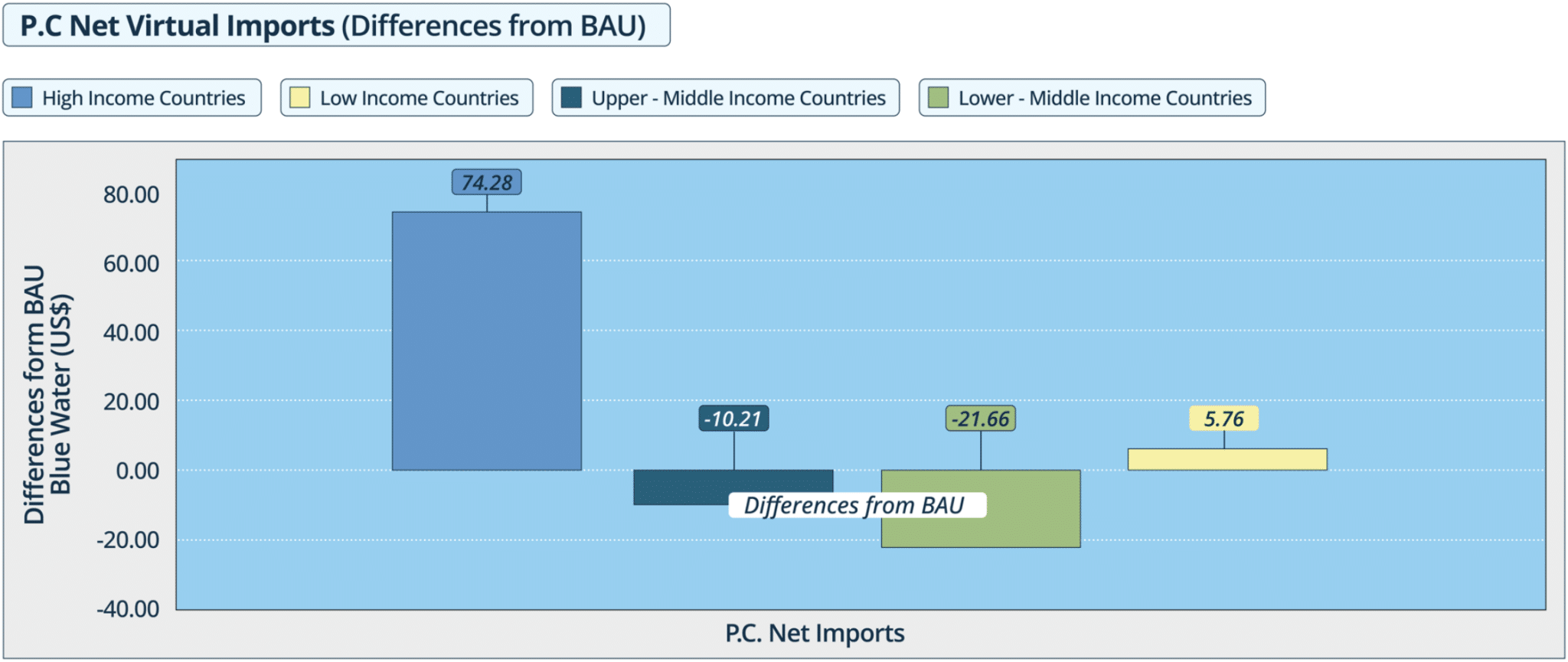

With the rapid changes and imbalances occurring in Earth systems, economies must consider a new dimension of freshwater’s impacts on economic development: namely, changes in precipitation as the ultimate origin of all freshwater, be it blue water in rivers, lakes and groundwater, or green water in soils and as evapotranspiration through plants. Global environmental change, particularly land-use and climate change, are altering the hydrological cycle at all scales, from local to global, increasing uncertainty in the year-to-year supply of stable precipitation. This affects all regions of the world, from temperate-cold to arid-hot hydroclimates, and impacts all economic sectors. In addition, as pointed out in Chapter 2, 40-60% of precipitation on land originates from Land-to-Land supply, not from Ocean-to-Land supply, which means the performance of neighbouring, upwind economies is a core factor in managing green-water-supplying ecosystems as sources for atmospheric moisture flows and precipitation downwind. Adding to these challenges, while the supply of water is becoming less stable, demand for it is rising exponentially with increases in living standards and demographic change. Water withdrawals have increased at twice the rate of population growth in recent decades (Dinar, 2024).

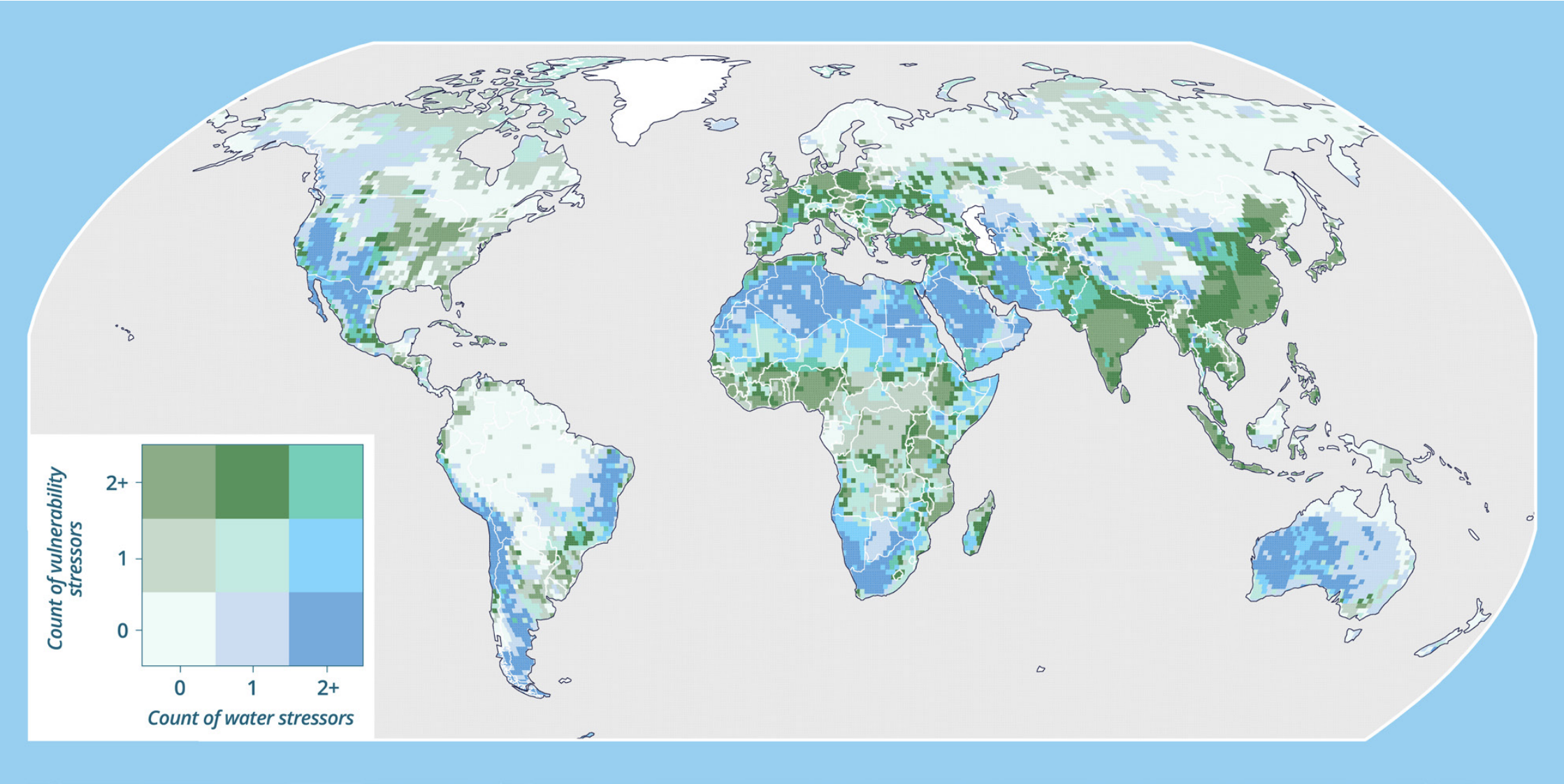

Together, these four dimensions – (1) the public-good nature of freshwater functions and services at all scales, (2) the interconnectedness of global change and local freshwater supply, and the resulting uncertainties, (3) the geographic interweaving of freshwater sourcing via atmospheric moisture flows, and (4) the increasing demand for freshwater – call for a fundamental shift in the way freshwater stresses are assessed and managed.

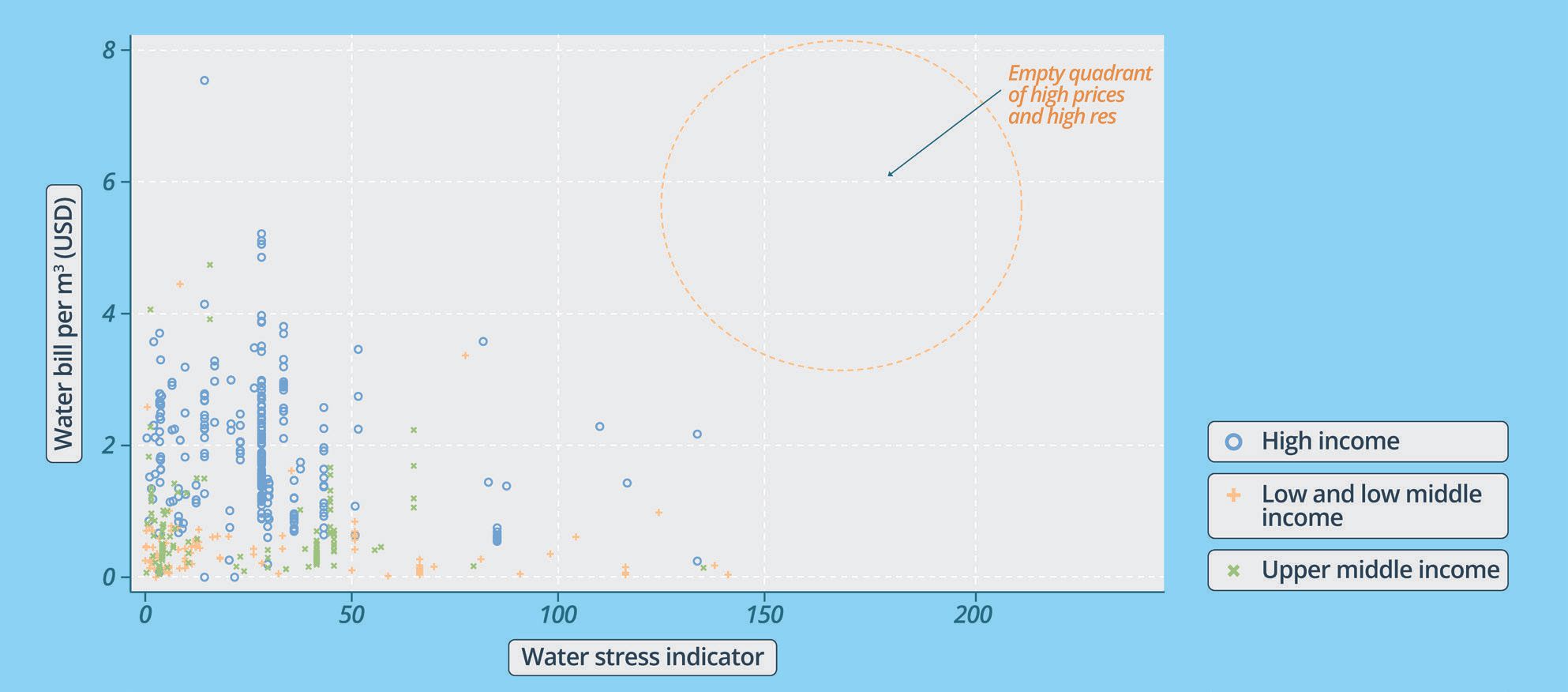

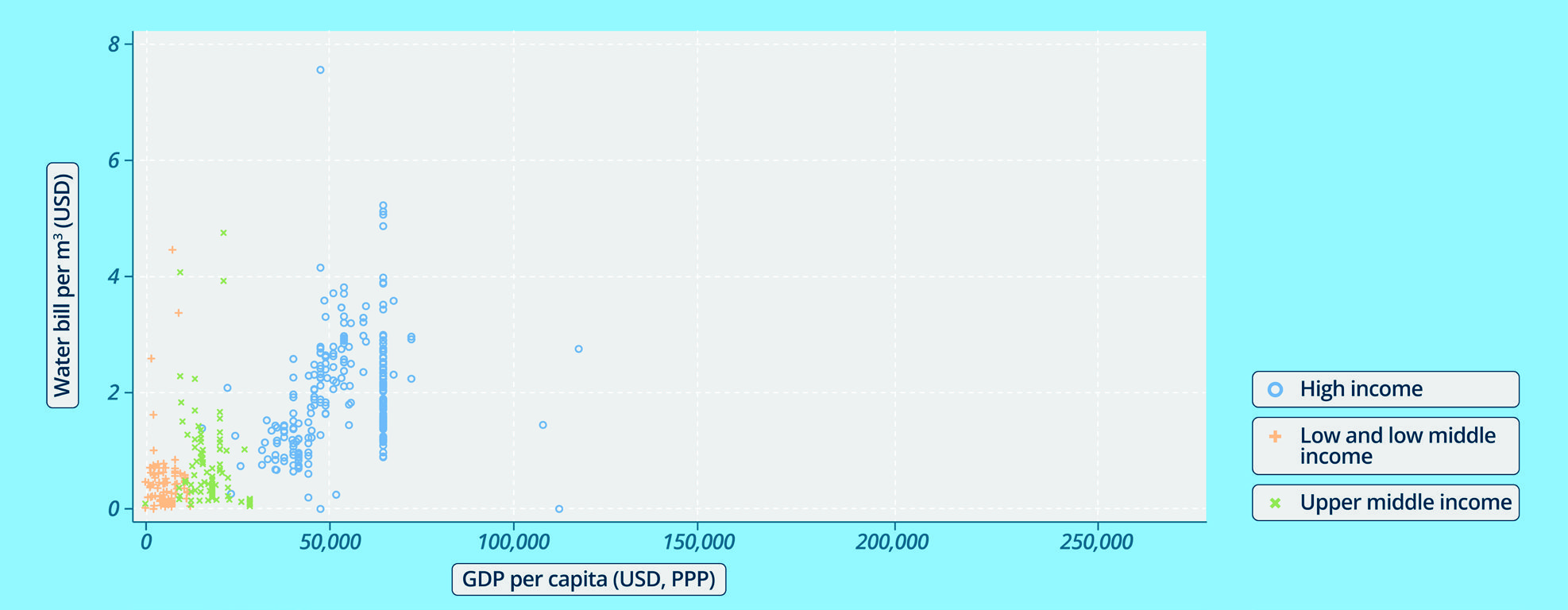

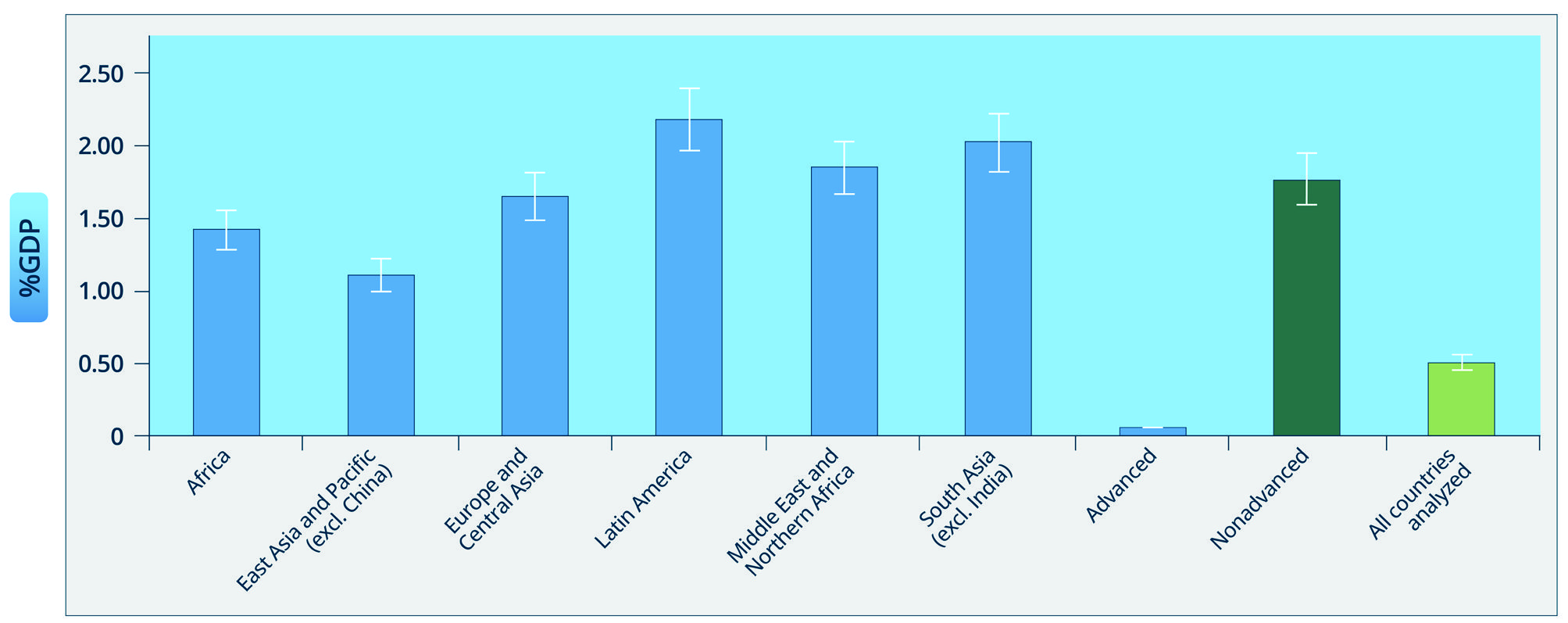

Current water policies are not designed to address pressures of such scale and magnitude, and often inadvertently exacerbate the degradation of water resources. Policies seldom allocate water in ways that reflect the types of value it creates, while subsidies often encourage water-intensive industries to locate in regions where water is already scarce. Nor have costly investments in water storage and infrastructure provided lasting relief. When the supply of water is increased without corresponding incentives, demand rises to meet the new level of supply, resulting in a higher level of water dependence and inefficiency. Powerful economic forces have transformed well-intentioned policies, into documented failures.

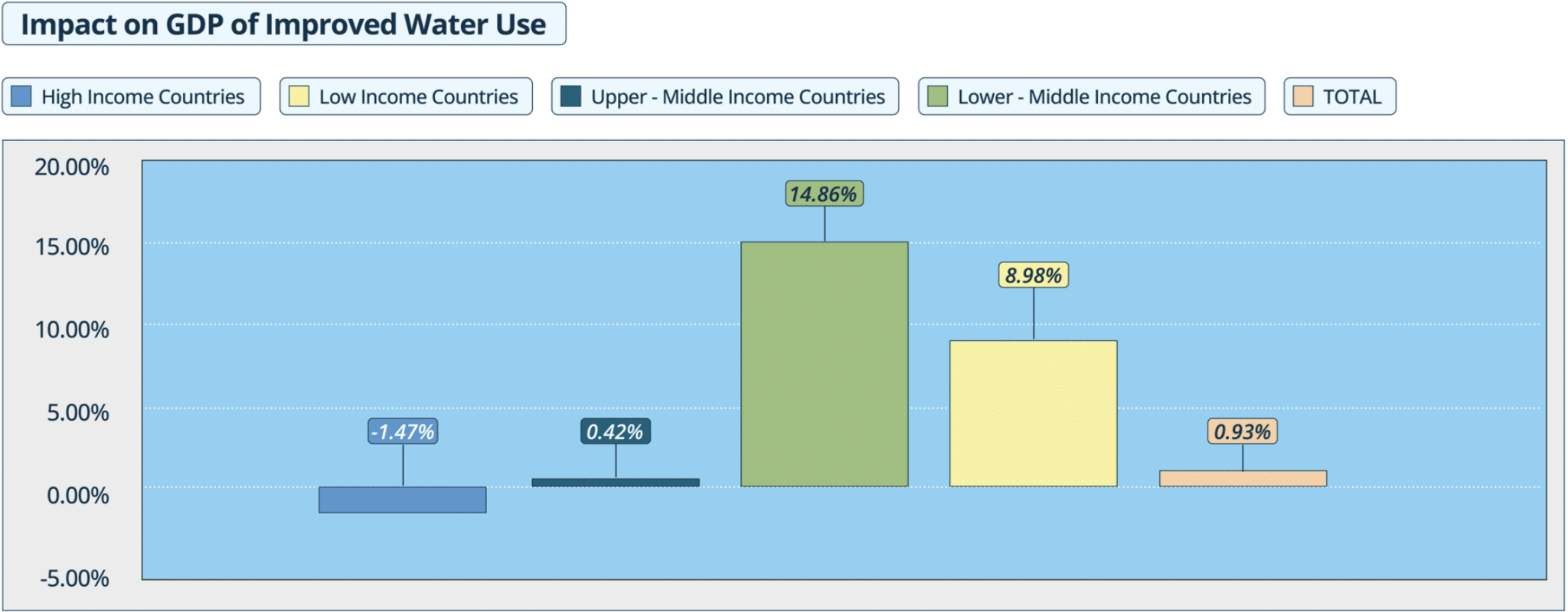

Adjusting to the new realities will call for significant reforms built on three overarching principles: the need to (1) value water for the critical economic, environmental, and social services it provides; (2) establish absolute limits to the amount of water that can be used safely and sustainably; and (3) implement policy packages to address trade-offs and achieve the triple goals of economic efficiency, equity, and environmental sustainability.

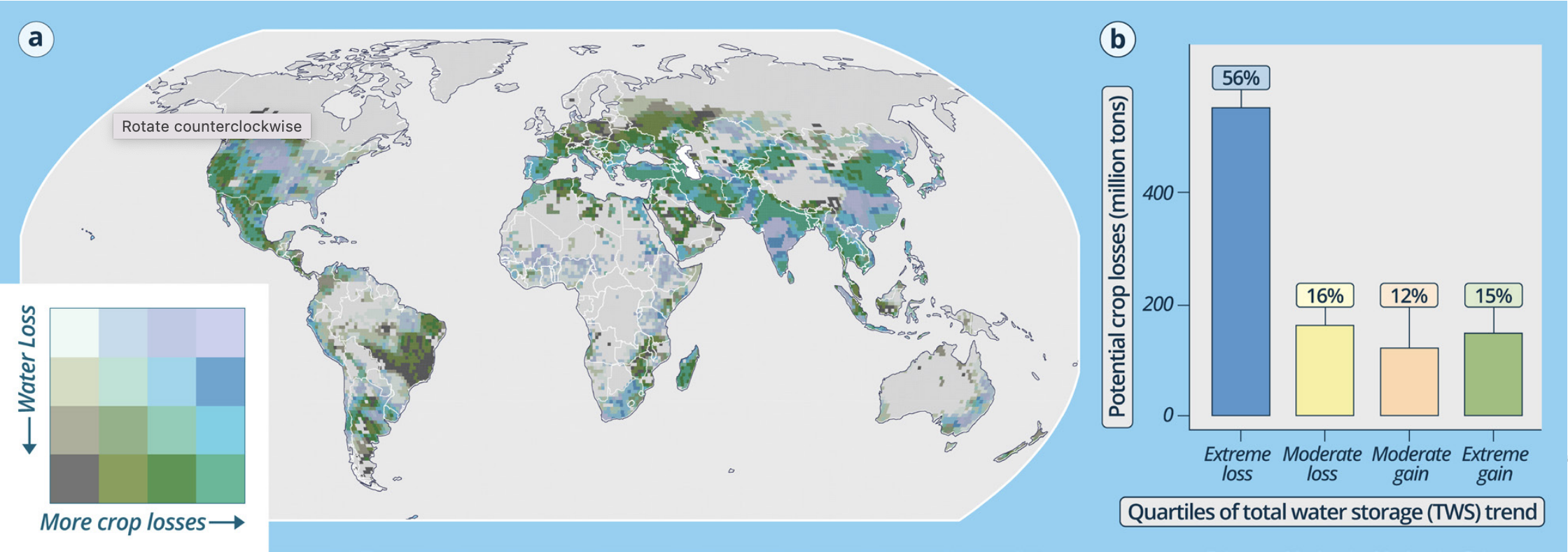

Translating these principles into effective policies will be challenging. It will be necessary to first identify where water-related risks and hotspots are most severe, then to understand what drives these changes – natural forces such as temperature and rainfall, or profligate management practices – and finally to assess the costs of inaction to determine whether reforms and changes that entail trade-offs are warranted. This chapter provides information to help answer these questions.

The first part of the chapter explores the effects of blue and green water on well-being, providing new estimates of the incidence and magnitude of impacts. It focuses on the economic significance of atmospheric moisture flows, since their contribution is not known despite accounting for 40-60% of rainfall. The second part of the chapter deals with blue water management and outlines the broad contours of a policy approach to achieve greater efficiency, equity, and environmental sustainability.